The official report from 1959 was brief, clinical, and final.

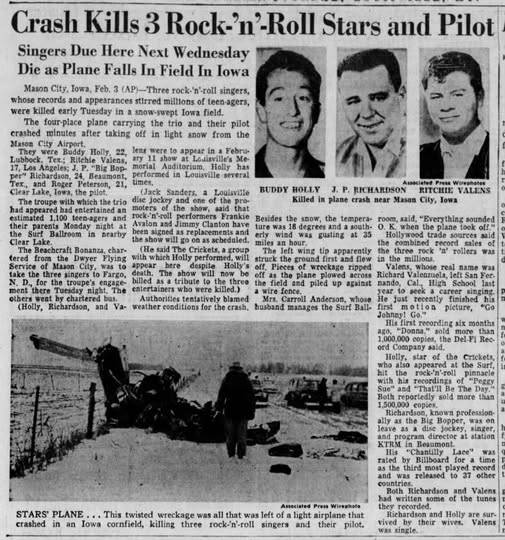

Buddy Holly. Ritchie Valens. J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson.

Killed when their small charter plane crashed into a frozen Iowa field.

Case closed.

But the land itself told a story that never fully fit the paperwork.

For decades, investigators, aviation experts, and historians have quietly revisited the crash site details—not to sensationalize the tragedy, but because certain elements never sat right. According to the original report, all three musicians were “thrown from the aircraft” upon impact. On paper, that explanation seemed straightforward. Violent crash. Severe impact. Bodies ejected.

Yet when later researchers examined declassified crash photographs and coroner records, that clarity began to fracture.

When Physics Doesn’t Behave as Expected

Aircraft crashes are chaotic—but not random.

Even in devastation, physics leaves patterns.

Seasoned investigators know that ejection from a small aircraft follows predictable rules: trajectory, distance, debris alignment, and injury consistency. When those rules are violated, questions arise.

And in the case of February 3, 1959, they did.

The locations where the bodies were found raised immediate red flags for later analysts. The distances from the wreckage varied in ways that didn’t match a single point of violent ejection. One body lay significantly farther than expected. Another was positioned at an angle inconsistent with the aircraft’s documented direction of travel.

These weren’t dramatic contradictions—but they were precise ones. The kind that makes professionals pause.

Injuries That Didn’t Add Up

Even more unsettling were the injuries—or, in some cases, the lack of them.

Certain trauma patterns typically associated with high-velocity ejection were either absent or inconsistent. Some injuries suggested sudden deceleration rather than explosive separation. Others hinted at forces applied differently than described in the official narrative.

Quietly, some investigators admitted what they wouldn’t say publicly:

This crash didn’t behave the way it should have.

That doesn’t mean conspiracy. It means uncertainty.

The Frozen Field and the Question of Movement

Another detail continues to haunt researchers: the possibility of post-impact movement.

In crashes involving frozen terrain, bodies often remain where physics leaves them. Sliding is minimal. Dragging is obvious. And yet, subtle positioning details in the photos suggested something else entirely—patterns that implied motion after impact.

Was it survivability for mere seconds?

Was it involuntary movement?

Or was the original reconstruction simply wrong?

The official report never explored those questions.

Why These Questions Were Never Pursued

In 1959, aviation investigation was not what it is today. Technology was limited. Time pressures were immense. And there was little appetite to prolong the pain surrounding the deaths of three young music stars.

The simplest explanation became the accepted one.

And once history settles on a narrative, revisiting it becomes uncomfortable.

A Tragedy Still Breathing Beneath the Surface

To be clear: no credible researcher claims the crash wasn’t fatal or that the outcome would have changed. The tragedy is absolute.

But the details—the final seconds, the mechanics of impact, the human moments at the end—remain unresolved.

That unresolved space is what haunts people.

Because history isn’t just about what happened.

It’s about whether we truly understand it.

Why It Still Matters

Buddy Holly wasn’t just a musician. He was a turning point in modern music. Ritchie Valens was 17 years old. The Big Bopper was a father.

When legends die young, we want closure. And when closure feels incomplete, questions linger—not out of morbid curiosity, but out of respect.

The frozen Iowa field may never give up its final secrets.

But the silence it left behind still echoes.

The official report from 1959 was brief, clinical, and final.

Buddy Holly. Ritchie Valens. J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson.

Killed when their small charter plane crashed into a frozen Iowa field.

Case closed.

But the land itself told a story that never fully fit the paperwork.

For decades, investigators, aviation experts, and historians have quietly revisited the crash site details—not to sensationalize the tragedy, but because certain elements never sat right. According to the original report, all three musicians were “thrown from the aircraft” upon impact. On paper, that explanation seemed straightforward. Violent crash. Severe impact. Bodies ejected.

Yet when later researchers examined declassified crash photographs and coroner records, that clarity began to fracture.

When Physics Doesn’t Behave as Expected

Aircraft crashes are chaotic—but not random.

Even in devastation, physics leaves patterns.

Seasoned investigators know that ejection from a small aircraft follows predictable rules: trajectory, distance, debris alignment, and injury consistency. When those rules are violated, questions arise.

And in the case of February 3, 1959, they did.

The locations where the bodies were found raised immediate red flags for later analysts. The distances from the wreckage varied in ways that didn’t match a single point of violent ejection. One body lay significantly farther than expected. Another was positioned at an angle inconsistent with the aircraft’s documented direction of travel.

These weren’t dramatic contradictions—but they were precise ones. The kind that makes professionals pause.

Injuries That Didn’t Add Up

Even more unsettling were the injuries—or, in some cases, the lack of them.

Certain trauma patterns typically associated with high-velocity ejection were either absent or inconsistent. Some injuries suggested sudden deceleration rather than explosive separation. Others hinted at forces applied differently than described in the official narrative.

Quietly, some investigators admitted what they wouldn’t say publicly:

This crash didn’t behave the way it should have.

That doesn’t mean conspiracy. It means uncertainty.

The Frozen Field and the Question of Movement

Another detail continues to haunt researchers: the possibility of post-impact movement.

In crashes involving frozen terrain, bodies often remain where physics leaves them. Sliding is minimal. Dragging is obvious. And yet, subtle positioning details in the photos suggested something else entirely—patterns that implied motion after impact.

Was it survivability for mere seconds?

Was it involuntary movement?

Or was the original reconstruction simply wrong?

The official report never explored those questions.

Why These Questions Were Never Pursued

In 1959, aviation investigation was not what it is today. Technology was limited. Time pressures were immense. And there was little appetite to prolong the pain surrounding the deaths of three young music stars.

The simplest explanation became the accepted one.

And once history settles on a narrative, revisiting it becomes uncomfortable.

A Tragedy Still Breathing Beneath the Surface

To be clear: no credible researcher claims the crash wasn’t fatal or that the outcome would have changed. The tragedy is absolute.

But the details—the final seconds, the mechanics of impact, the human moments at the end—remain unresolved.

That unresolved space is what haunts people.

Because history isn’t just about what happened.

It’s about whether we truly understand it.

Why It Still Matters

Buddy Holly wasn’t just a musician. He was a turning point in modern music. Ritchie Valens was 17 years old. The Big Bopper was a father.

When legends die young, we want closure. And when closure feels incomplete, questions linger—not out of morbid curiosity, but out of respect.

The frozen Iowa field may never give up its final secrets.

But the silence it left behind still echoes.