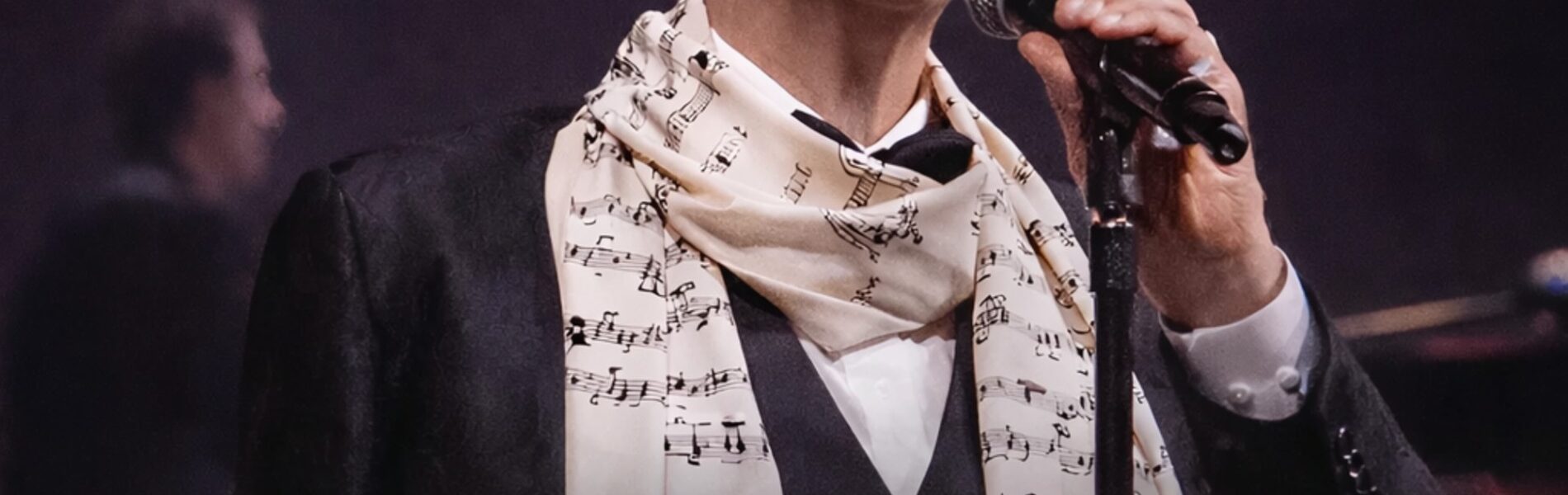

Andrea Bocelli steps onto a stage he cannot see, yet he knows exactly where he is.

He knows the distance between the piano and the conductor’s podium. He senses the height of the ceiling, the openness of the hall, the way sound will travel before he releases the first note. For Bocelli, performing has never depended on vision. It has depended on listening, memory, and an internal map built through years of discipline and trust.

Blindness did not remove his connection to the stage. It reshaped it.

From an early age, Bocelli learned to experience space through sound. Every room has a signature — a subtle echo, a resistance, a warmth. Large halls breathe differently from small theaters. Cathedrals carry notes upward, while opera houses return them gently. Long before an audience arrives, Bocelli listens. He lets the space introduce itself to him.

This is how he “sees” the stage.

Before each performance, Bocelli carefully memorizes the layout. He walks the stage slowly, counting steps, feeling textures beneath his feet, registering changes in air movement. He notes where the orchestra sits, how close the conductor stands, where the microphones are placed. These details are not minor to him; they are essential. They form a mental blueprint that allows him to move with calm confidence once the lights come up.

For Bocelli, memory replaces sight.

But it is not mechanical memory. It is emotional and sensory. He remembers not only where things are, but how they feel. The presence of musicians nearby. The quiet energy of the audience beyond the edge of the stage. The subtle cues that signal readiness — a breath from the conductor, a shift in posture from the orchestra.

When he begins to sing, he is already fully present in that invisible landscape.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Bocelli’s performances is how naturally he interacts with others on stage. He turns toward the conductor at precisely the right moment. He aligns seamlessly with the orchestra. He adjusts his dynamics instinctively, as if guided by something unseen. In reality, he is guided by sound — by the smallest changes in tempo, balance, and resonance.

Hearing, for Bocelli, is not passive. It is active, alert, and deeply trained.

He listens not only to the music, but to the space around it. He senses how his voice travels, how it returns to him, how it blends or separates. This constant feedback allows him to adjust in real time, shaping each phrase with precision. Where others may rely on visual cues, Bocelli relies on instinct sharpened by necessity.

He has often said that blindness did not limit his music — it sharpened it.

This statement is not poetic exaggeration. It reflects a lived reality. Without visual distraction, Bocelli’s focus narrows to what truly matters: sound, breath, and emotion. Every note must be intentional. Every pause must be felt. There is no reliance on gesture or expression to communicate meaning. The voice must carry everything.

This discipline gives his performances a rare clarity.

Audiences frequently describe Bocelli’s presence as calm, centered, almost meditative. That stillness comes from trust — trust in his preparation, trust in his collaborators, and trust in his internal sense of orientation. He does not rush. He does not overcompensate. He allows the music to unfold at its own pace.

There is also humility in this approach. Bocelli does not attempt to dominate the stage visually. Instead, he becomes part of a shared musical space. His awareness extends outward, encompassing the orchestra, the hall, and the listeners. This creates a feeling of inclusion — as if the audience is not merely watching, but participating in the experience.

Performing without sight requires a deep relationship with memory, but it also requires letting go. Bocelli prepares meticulously, yet once the performance begins, he releases control. He listens. He responds. He allows the music to guide him moment by moment.

This balance between structure and surrender defines his artistry.

It also explains why Bocelli’s performances feel so consistent across venues and contexts. Whether singing in an ancient cathedral, a modern arena, or an open-air setting, he adapts seamlessly. He does not need to see the grandeur to honor it. He hears it. He feels it.

For younger musicians and listeners, Bocelli’s approach offers a powerful lesson. Music is not about perfection or spectacle. It is about attention. About presence. About learning to listen deeply — to others, to space, and to oneself.

In a world saturated with visual stimulation, Bocelli’s artistry reminds us that sound alone can carry immense meaning. That listening is an act of imagination. That limitation, when met with patience and dedication, can become a source of strength.

Andrea Bocelli does not “overcome” blindness on stage. He incorporates it. He allows it to shape how he experiences music, how he connects with others, and how he communicates with the audience. His performances are not defined by what is missing, but by what has been refined.

When Bocelli sings, he does not look outward for guidance. He listens inward. And through that listening, he invites the world to hear more carefully as well.

That is the true art of performing without seeing.

Not the absence of sight,

but the presence of understanding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch/SU-7EmNSqag