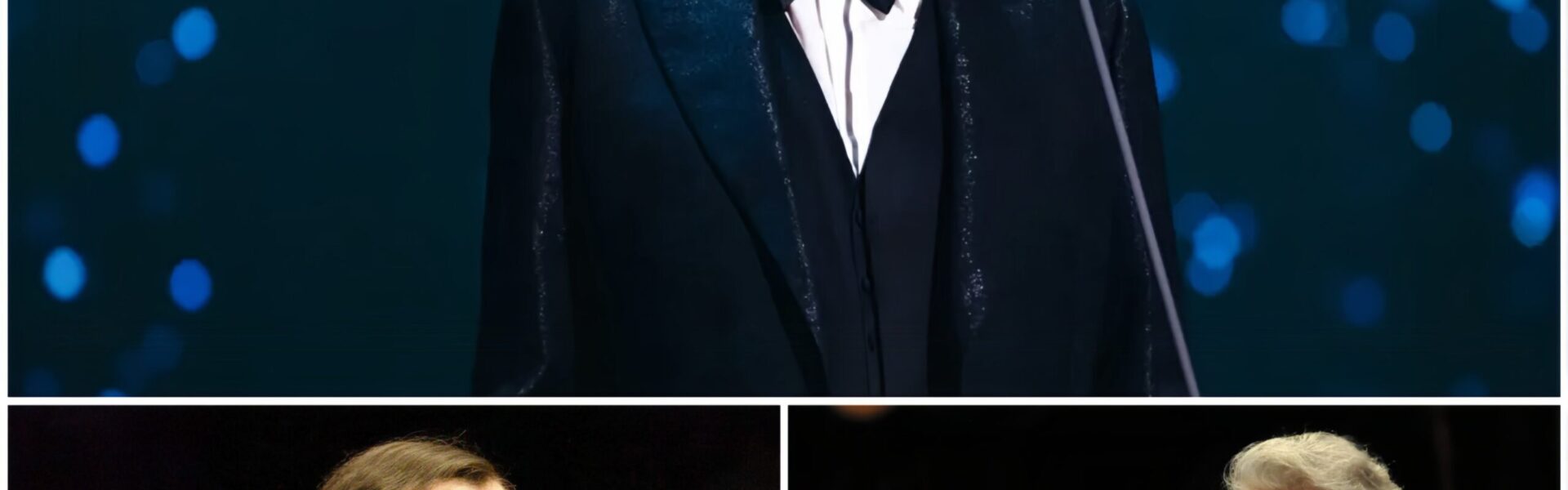

Few artists have been debated as intensely — and as persistently — as Andrea Bocelli. The question has followed him for decades, whispered in conservatories, written in critical reviews, and debated in academic circles: Is Andrea Bocelli a “true” operatic tenor?

On the surface, it appears to be a technical argument. Critics point to vocal classification, stylistic choices, and repertoire. They compare him to figures like Luciano Pavarotti and Plácido Domingo, measuring projection, phrasing, and adherence to operatic tradition. The verdict from some corners of the classical establishment has been dismissive: Bocelli is too crossover, too accessible, too popular to belong fully within the operatic canon.

Yet what makes this debate remarkable is not the criticism itself. It is Bocelli’s response — or rather, his refusal to respond.

While arguments continued around him, Bocelli did not enter the arena. He did not issue rebuttals. He did not attempt to redefine categories or defend his credentials. Instead, he kept singing. And in doing so, he reframed the conversation entirely.

Classical purists often approach opera as a protected space, governed by strict definitions and historical lineage. In this framework, deviation is treated as dilution. Bocelli’s career challenges this premise. His repertoire moves fluidly between opera, sacred music, and popular song. He performs in cathedrals and stadiums alike. To some, this versatility signals compromise. To others, it signals reach.

Bocelli never denied that his path differs from that of traditional operatic tenors. He simply questioned whether difference required justification.

When asked directly about classification, his answer has remained strikingly consistent: “I sing for people, not categories.”

This statement is not evasive. It is philosophical.

It suggests that music’s purpose lies not in fitting definitions, but in communication. That the value of a voice is measured not only by technique, but by its ability to reach, move, and connect. In this sense, Bocelli does not reject opera. He repositions it — not as an exclusive domain, but as a living language.

Comparisons to Pavarotti and Domingo often dominate the critique. These singers represent an era of operatic dominance rooted in tradition and institutional recognition. Bocelli, by contrast, emerged in a different cultural moment — one shaped by globalization, recording technology, and cross-genre audiences. To judge him by identical criteria is to ignore context.

More importantly, it assumes that opera itself must remain unchanged to remain valid.

Bocelli’s career quietly challenges that assumption. By bringing operatic technique into popular consciousness, he introduced millions to a sound they might otherwise never encounter. Many listeners discovered opera not through formal training, but through a voice that felt approachable. In this way, Bocelli did not weaken the tradition. He expanded its audience.

Critics argue that accessibility lowers standards. Bocelli’s success suggests the opposite: that high-level artistry can coexist with emotional clarity. His voice may not conform to every academic expectation, but it carries something equally demanding — restraint, sincerity, and intention.

And while purists debated, audiences listened.

This is where the debate becomes asymmetrical. One side argued definitions. The other side — Bocelli — continued to build a body of work that resonated globally. He did not need to win critical approval to establish artistic legitimacy. His legitimacy emerged through sustained connection with listeners.

There is also a deeper humility in Bocelli’s approach. He does not present himself as a challenger to operatic giants. He does not claim supremacy. He occupies his own space, acknowledging tradition while refusing to be confined by it. This quiet confidence disarms criticism without confronting it.

In avoiding direct engagement, Bocelli achieved something rare: he removed ego from the argument. By refusing to fight over labels, he exposed their limitations. The debate continued, but its relevance diminished.

Opera, after all, was never meant to be a museum piece. It was born as popular art, intended to move broad audiences. Bocelli’s career, paradoxically, returns opera to this origin — not by simplifying it, but by humanizing it.

The purist critique assumes that artistic value is preserved through exclusion. Bocelli’s legacy suggests that value is preserved through relevance. Not through rigidity, but through resonance.

And perhaps this is why, decades into his career, the debate persists — but feels increasingly detached from reality. Bocelli continues to perform, to record, to reach new generations. His voice remains recognizable, not because it fits a category, but because it carries intention.

In refusing to argue, Bocelli made the argument irrelevant.

He did not win by out-singing critics.

He did not win by redefining opera.

He won by choosing purpose over position.

The question “Is Andrea Bocelli a true operatic tenor?” may continue to circulate. But the answer, for millions of listeners, has already been given — not in words, but in experience.

Andrea Bocelli did not sing to satisfy categories.

He sang to be heard.

And in doing so, he changed the conversation without ever joining it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch/noy7DRMB7CE