Jeff Allen holds Alabama together with experience, creativity and an urgency to stay on the ‘cutting edge’

Handing out game balls from Alabama’s dramatic come-from-behind 34-24 win at Oklahoma in the first round of the College Football Playoff wasn’t easy. There were so many candidates to choose from: Ty Simpson had his best performance at quarterback in more than a month and a half; Lotzeir Brooks scored his first and second career touchdowns; Zabien Brown notched his second pick-six of the season; and Keon Keeley had a breakout performance off the bench with a sack and two pressures.

But there was another person who deserved a shoutout — not a player and not even a coach. Defensive coordinator Kane Wommack brought this individual up unprompted in the post-game press conference. So did offensive coordinator Ryan Grubb. A few days later, while previewing Thursday’s Rose Bowl vs. No. 1 Indiana, coach Kalen DeBoer mentioned this unsung hero in his opening statement.

“I’ve got to give a tip of the hat to our training staff and our doctors,” DeBoer said. “Jeff Allen, who runs our training room downstairs with his staff, [did] an amazing job just putting people together and getting guys as healthy as they could have.”

Earlier this month, Alabama was beginning to resemble “The Walking Dead” with more than a dozen key players either out or playing through injuries in an SEC Championship Game loss to Georgia. But many of those same players, including starters like Jam Miller, Josh Cuevas and Kam Dewberry, recovered enough to contribute in the win over Oklahoma. That’s thanks in large part to the work of Allen, the team’s head athletic trainer since 2007.

Former Alabama assistant Mike Locksley once told ESPN, “If Nick Saban is the soul of Alabama football, then Jeff Allen is the glue that keeps it together.”

Last week, I called the man who was named Head Athletic Trainer of the Year by the National Athletic Trainers Association in 2018.

“What’s going on?” I asked Allen.

“Oh, we’re just trying to heal some bodies,” he said. “I feel like Humpty Dumpty in here, just putting them back together again.”

We both laughed.

I asked when’s the last time he had a day off.

“That’s a good question,” he said.

He had to think about it.

“Umm,” he said. “Probably the bye week. Is that right? Golly. That’s crazy.”

After eight-straight weeks on, Allen took Christmas Day off.

But the next day, it was back to work as Alabama resumed practice. Which meant more wrapped ankles and shoulders and knees, and braces, and hours upon hours in the training room.

Allen thinks they’re fortunate, though. The football team has eight certified athletic trainers. Most teams, he said, have 5-6.

The structure Allen has built is unique. A few years ago, he noticed they were having too many conversations about who would be tending to which specific players. The last thing he wanted, he said, was “some player not knowing who’s taking care of them.” So, Allen decided, “Let’s create a football coaching model and let’s apply it in the medical care.”

Jakob Grieff coordinates the offense along with assistant Zarien Hood; Paige Hudson coordinates the defense along with assistant McKennah Sigler; and Rob Sun coordinates special teams.

The specialization creates efficiency.

“I don’t know that people really fully appreciate the thought that goes into that Saturday-to-Saturday model,” he said. “We start as soon as the game is over — really we’re keeping track of what we’re getting during the game and then what are we going to do with that particular player post-game, right then. That’s going to give us a chance to get them better before the next Saturday.

“You have to think that way because every second is going to matter in this league in terms of turning a player around from from one Saturday to the next.”

Long-term care (see: rehab) is under the purview of associate head athletic trainer Jeremy Gsell.

Allen also created a new position: director of player well being. He assigned Paige Ruden, a former intern who went on to work in the NFL with the Indianapolis Colts, to the role, which allows the coordinators and their assistants to focus on getting players ready for games while Ruden is tasked with considering the big picture of injury prevention. That means working closely with the weight room and combing through data gathered from wearable GPS devices, hoping to spot troublesome trends before they result in an injury.

“Football is not a contact sport. This is a collision sport,” Allen said. “And we know that with collisions, there’s going to be injuries, there’s going to be trauma. But, honestly, what we are hyper focused on is soft-tissue injuries — hamstring strains, groin strains, hip flexors, all those things that you hear about. We want to control those because those are things that we feel like we absolutely can control. And that’s where that position is helpful. The weight room is going to tell them, ‘Hey, we’re seeing this on a particular player or we’re seeing that.’ And then Paige is going to turn around and work with that player and do some one-on one-work with them during the week or during the season, while those coordinators are focused on Saturday to Saturday.”

Allen likes what the data is telling him. Before the SEC title game, he said, they averaged 95% game availability (how many players can participate). They’ve “absolutely” seen a decrease in soft-tissue injuries, he said, “By her taking the information that they’re gathering in the weight room and applying it in here when we need to do some specialized rehab.”

It’s a team effort. When DeBoer tipped his cap to Allen last week, he also name-dropped team physicians Dr. Norman Waldrop, Dr. Lyle Cain and Dr. Ray Stewart. Strength coach David Ballou needed credit, too, he said, reporting, “We had as many guys hit their top speeds [against Oklahoma] as we have since the Tennessee game, and that’s tied for the most over 20 miles an hour all year.”

“We take how we treat our players really serious because you need every competitive edge you can get in this conference,” Allen said. “You sit there and look at a program and you think, ‘Man, why can’t they win? What is wrong with them? They have everything that they need. Why are they not successful?’ If your best players aren’t on the field, it’s hard to win consistently. So we take a lot of pride in that.”

Another area they take pride in: innovation.

Alabama was able to source TayCo ankle braces for players like Cuevas. The unique over-the-shoe device features Kevlar reinforced straps and hinges that limit mobility while providing stabilizing support. Cuevas, who was a game-time decision with a foot injury, wound up playing 28 snaps against Oklahoma, catching three passes for 35 yards.

Another example: after finding out the hard way about Oklahoma’s unique lighting, which contributed to several dropped passes last season, Alabama bought so-called “strobe goggles” from Senaptec to practice with.

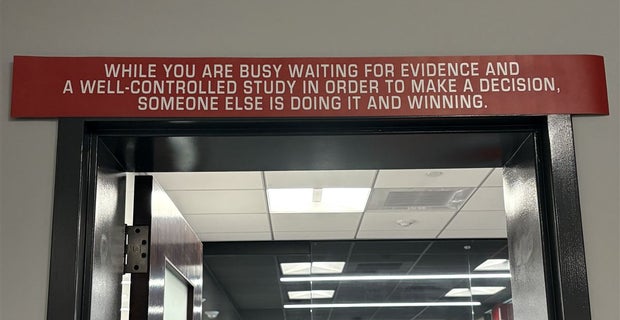

While talking about all of this, Allen snapped a quick photo and sent it via text message. It showed a red-and-white sign hanging above the doorway leading out of his office: “While you are busy waiting for evidence and a well-controlled study in order to make a decision, someone else is doing it and winning.”

“I always wanted to remind myself that we have to be on the cutting edge,” he said. “If you’re going to work at a place like Alabama, you have to constantly be looking for ways to make the program better.”

Allen has been doing this work for more than three decades.

“But sometimes experience can be a detriment because you can get caught in how you’ve always done it,” he said. “And I don’t ever want to do that. Even if that way works, there might be some better things and some tweaks we can make. And I think it goes back to what I said about the art of doing this job. You have to keep an open mind, and you have to have a creative mind, too, thinking outside the box.

“I think that quote kind of sums up our philosophy here. I’m not going to wait on some research to tell me if something’s going to work. The research that I’m going to use is, Does it make the player feel better? Do they notice a difference? And I think being open minded like that has been beneficial for us.”

Allen recalled the TightRope procedure Waldrop helped popularize. Back in 2015, former Alabama left tackle Cam Robinson suffered a high-ankle sprain — an injury at the time viewed as likely season-ending. Instead, Waldrop operated using the new method and Robinson was back in two weeks. The procedure has since become the gold standard for treating high-ankle sprains.

And let’s be clear about one thing: this all costs money.

Staffing alone for trainers — based on some quick back-of-the-napkin math — comes out to about $1 million per year. Allen said he doesn’t know his exact operating budget, and with good reason.

“That is because of Alabama. That’s because of our administration — our AD, president, board of trustees,” he said. “I have never, ever been told no when it comes to taking care of players and doing the right thing for them. Ever. Ever. Ever. No one has ever questioned what we’re doing because it costs too much.”

That mindset was apparent from Day 1. Allen can still remember meeting with then-athletic director Mal Moore in the summer of 2007 and being told, “Your responsibility is to keep our players healthy and I’m never going to get in the way of that for any reason. I’ll always support you. This place will always support you. And we expect you to do your job at a high level.”

“That mentality,” Allen said, “that philosophy, from our administration has always remained the same. When you’re a part of an organization that does it that way, it really makes a difference. Because I know not every place is like that. They’re looking at, ‘Gosh, how much are we spending on this or that?’

Speaking of 2007, I asked Allen whether as the last remaining member of Nick Saban’s inaugural staff if he considered retiring when Saban hung up his straw hat and whistle two years ago.

Point-blank, I asked him, “How much longer do you want to do this?”

“I’ve had other opportunities and other things that came before me,” Allen said. “NFL opportunities. But, man, this place is special. I almost don’t have the words for it. It’s a really hard place to leave. And I’ve always felt that because of the passion people have for the program.”

He thinks about Mal Moore, Finus Gaston, Bill McDonald — people who were the bedrock of the university and would tell him about the halcyon days of Paul “Bear” Bryant. Allen has studied the history of Wallace Wade and Frank Thomas. He cherishes having been part of Saban’s dynastic run.

“We’re caretakers of a very special program, and it’s our responsibility to keep it going,” he said. “You asked, how much longer? That’s a great question. I’m 54. I don’t feel old. And I think one reason I don’t feel old is because I’m around 18-20 year olds every single day, and that tends to keep you younger. But I still love what I do. I love the relationships with the players. And having been here as long as I have, one thing that’s really cool is to see all these former players come back.”

Another thing keeping Allen in Tuscaloosa: his relationship with Ballou and DeBoer.

Ballou, Allen said, “is the best strength coach in football, not in college football.”

The alignment they have, from head football coach to strength coach to head trainer, is crucial to the program’s success.

“I think the world of [DeBoer],” he said. “I love how he builds relationships with our players. You can see that with the retention we’ve been able to have. When you’re seeing constant turnover at other places, we’re not not seeing that as much. Because I know — I don’t think, I know — that our players love playing for him, and they love the culture, and they love the atmosphere that we have here, and that means a lot.”

Allen doesn’t say it, but he’s a crucial piece of that as well. He’s become part of the bedrock of Alabama.

He’s in the building every day, making sure things don’t fall apart.