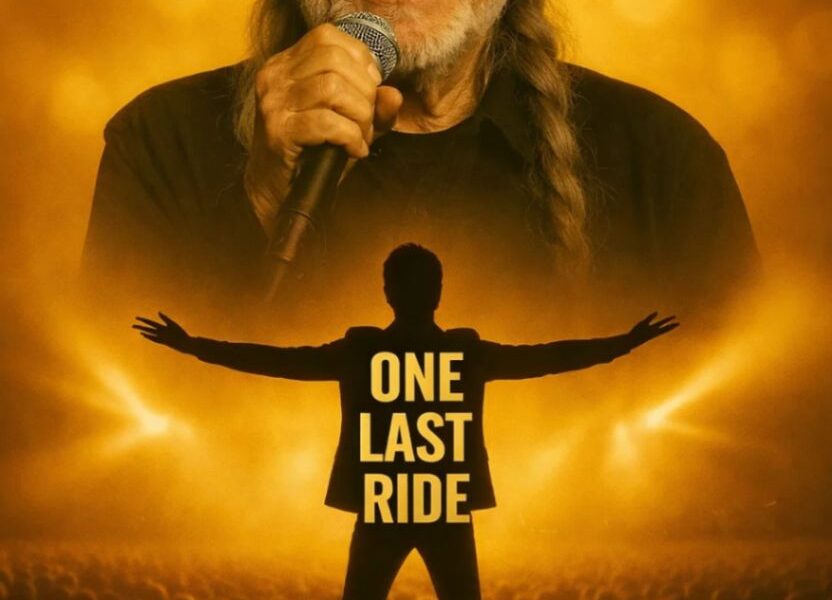

“ONE LAST RIDE” — WILLIE NELSON’S FINAL TOUR JUST GOT REAL It started with a whisper — a few quiet words from his team in Austin.

The first light of dawn crept over the Colorado River like a reluctant confessor, casting long shadows across Willie Nelson’s Luck Ranch—a 700-acre sprawl of pecan groves, weathered barns, and stages stained with decades of smoke and stories. It was here, in the quiet cradle of his outlaw empire, that the whisper began: a few hushed words from his inner circle, leaked like a bootleg tape from a ’70s honky-tonk. By sunrise, the news detonated across Nashville’s airwaves and Austin’s coffee shops: Willie Nelson, the Red-Headed Stranger himself, the 92-year-old poet laureate of American music whose braids and battered Martin guitar have outlasted presidents and prohibitions, is hitting the road one last time. “One Last Ride: The Final Outlaw Tour,” they called it—40 dates across the heartland, from the Ryman Auditorium to Red Rocks, kicking off New Year’s Eve at the Austin City Limits. But this isn’t just another victory lap for a man who’s sold 50 million records and survived more scandals than a soap opera. Insiders murmur of something deeper, a secret Willie has cradled close for years. This farewell to the blacktop? It’s not merely to the miles. It’s to someone. And in the telling, every chord, every yarn spun under stage lights, will carve a little deeper into the soul of country music.

Willie Hugh Nelson arrived at the press conference like a specter from a sepia photograph—lean as a lariat, eyes twinkling with that impish glint that once dodged the IRS and ignited Woodstock’s back forty. Flanked by family (sisters Bobbie on keys, son Lukas strumming shotgun), he eased into a director’s chair on the ranch’s outdoor pavilion, joint unlit but ever-present in his shirt pocket. A light breeze rustled the live oaks, carrying the faint twang of a distant pedal steel. “Folks,” he drawled, voice a gravelly whisper honed by 70 years of warbling and weed, “I’ve been ridin’ this pony since Korea was a worry and Elvis was a kid.

She’s carried me through hellhounds and heaven-sent harmonies. But every trail has an endin’. This tour? It’s my way of sayin’ ‘howdy’ and ‘so long’ proper-like.” The crowd—journalists from Rolling Stone to Texas Monthly, superfans clutching faded Stardust vinyls—leaned in, sensing the weight beyond the words. Tickets sold out in 17 minutes; secondary markets hit $5,000 a seat. But as Willie paused, fiddling with his bandana, the air thickened. “And it’s for her,” he added softly, gaze drifting to the horizon. “Always has been.”

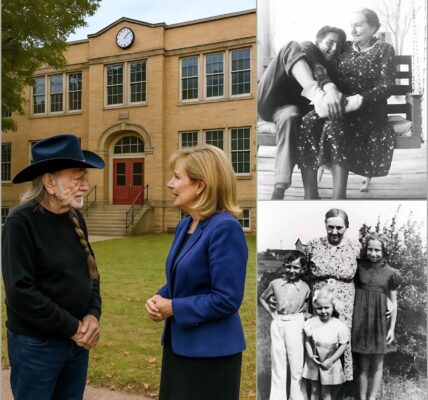

The “her” is the secret that’s shadowed Willie’s legend like a half-smoked cigarette—the ghost of Martha Jewel Matthews, his first love, the farm girl from Abbott, Texas, who captured his 10-year-old heart in a one-room schoolhouse and held it through the dust of the Depression. They were kids in love before love had a name: Willie penning his first poems on her behalf, Martha trading wildflowers for stolen kisses behind the cotton gin. War tore them asunder—Willie enlisting in ’52, shipping to Austin while she waited, letters yellowing like old sheet music. He returned a changed man, guitar in hand, dreams of Nashville burning brighter than the scars of separation. They married in ’53, a shotgun affair at 20, birthing daughters Lana and Susie amid the chaos of cotton fields and club gigs. But the road, that jealous mistress, pulled him away—nights in smoky dives, days chasing radio play. By ’59, Martha filed for divorce, the papers served while Willie was mid-set in Fort Worth. She vanished into anonymity, remarrying a rancher, raising the girls in Waco’s quiet folds. Willie? He spiraled: second wife Shirley, third Connie, fourth Annie (still by his side at 91), eight kids scattered like seeds in the wind. But Martha lingered—a phantom verse in “Hello Walls,” the ache in “Crazy,” the what-if woven into every “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.”

Insiders—those who’ve warmed Luck’s hearths and shared Willie’s sacramental herb—say the truth surfaced last winter, during a flu that sidelined him for months. Confined to the ranch, oxygen mask fogging his view, Willie rifled old boxes: yellowed photos of Martha at 16, braids mirroring his own; a lock of her hair tied with twine; letters unread since Truman’s time. “She wrote once, after the divorce,” he confided to Trigger magazine’s editor over rye whiskey. “Said, ‘Willie, you chase the horizon, but home’s the hill we rolled down together.’ I folded it away, thinkin’ time would blur the ink.” It didn’t. Martha, now 91 herself, lives reclusively in a Waco assisted living home, frail from arthritis but fierce in memory—Alzheimer’s nibbling edges, but her laugh, they say, still echoes like a steel guitar slide. Willie visited last spring, unannounced, Lukas driving the old ’57 Chevy. They sat on her porch swing for hours, hands clasped, trading stories of what-ifs. “She remembered every lyric,” Lukas later shared on his Lukas Nelson & Promise of the Real podcast. “Dad cried—first time I saw it. Said, ‘This tour’s gotta honor that. Bring her stories full circle.'”

And so, “One Last Ride” was born—not as defeat, but as devotion. The setlist? A tapestry of firsts: “Family Bible,” the gospel hymn Willie sold for $50 in ’59 to feed his babies (Martha’s babies); “Night Life,” the blues he hawked anonymously before fame’s floodgates; rarities like “What Can You Do to Me Besides Be Gone,” a deep cut from his 1962 pawn-shop days, penned in the shadow of their split. Guest stars queue like pilgrims: Bob Dylan trading verses on “Gotta Serve Somebody” (a nod to their ’76 Rolling Thunder Revue); Merle Haggard’s hologram for “Pancho and Lefty” (Willie’s 1983 duet with his fallen friend, but tonight, a proxy for lost loves); even Taylor Swift, whispering harmonies on “Always on My Mind,” her eyes misty for the mentor who blessed her 2023 Grammys speech. Each night ends with “The Circle Be Unbroken,” Bobbie at piano, the crowd’s lighters (and phones) a field of fireflies, Willie’s voice cracking on the bridge: “Will the circle be unbroken / By and by, Lord, by and by.”

But the circle’s closure cuts deepest in the unscripted. Willie plans “porch stops”—impromptu acoustic sets at Waco’s old schoolhouse, Abbott’s cotton fields, the Hillbilly Cafe where he busked as a teen. Martha’s invited, wheelchair and all, front row for the homecoming. “It’s not morbid,” insists Micah Nelson, Willie’s youngest, a painter whose murals adorn the tour buses. “Dad’s 92—docs give him years, not months—but he’s choosin’ now. To say what the miles stole.” Health whispers swirl: the emphysema that forced a 2023 tour scrub, the pacemaker ticking like a metronome. Yet Willie’s defiant—yoga at dawn, farm-fresh greens, that “special herb” for inflammation. “Outlaws don’t fade; we fox-trot into the fog,” he quipped at the presser, sparking laughs that masked the lump in every throat.

The announcement’s wake has been a whirlwind of wonder and woe. #WilliesLastRide trended for 72 hours, amassing 4.2 million posts: fans booking flights from Oslo to Omaha, tribute murals blooming in Nashville’s alleyways. Willie Nelson & Family’s site crashed twice; charity tie-ins flood the pot—proceeds to Farm Aid (co-founded by Willie in ’85) and the Waco Senior Center, where Martha volunteers when her hands allow. Skeptics snipe—”PR ploy for the docuseries”—but those who’ve shared Willie’s tour-bus confessions know better. “He’s grievin’ forward,” says producer Buddy Cannon, architect of Last Man Standing (2024’s raw confessional). “Martha’s the root. The road was the branch that bent ’em apart. This straightens it.”

For a man who’s thumbed his nose at Nashville’s suits (signing to Columbia in ’75 after Atlantic flamed out), dodged the feds (that 1990 tax-evasion odyssey, absolved by The IRS Tapes), and legalized his sacrament (Texas compassion-use bill, 2021), this vulnerability is revolutionary. Willie’s life: a rogue’s gallery of reinvention—from Bible salesman to tax fugitive, pot prophet to Farm Aid founder. Marriages crumbled under tour’s tyranny; kids navigated the fallout (Lana’s estrangement, reconciled in ’05). Yet through it, music as mender: “On the Road Again” (1980’s road-dog anthem, co-written with Bob Dylan in a kitchen jam); Red Headed Stranger (1975’s concept opus, birthed in divorce’s ashes). Now, the finale reframes it all—a valentine to the girl who sparked the fire.

As the tour buses rev for rehearsals—vintage Airstreams trailed by solar-powered semis—Willie slips away to the ranch’s chapel, a tiny adobe where he marries couples and mourns alone. There, under stained-glass longhorns, he strums “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground,” eyes shut against the sting. “She’s the someone,” he told Annie last night, her hand in his. “The ride ends where it began—with her.” For fans, it’s elegy and exhortation: Buy the ticket, take the ride, love fierce before the curtain. Every song will hit different—laced with loss, luminous with legacy.

Willie Nelson doesn’t do encores; he does eternities. “One Last Ride” isn’t goodbye; it’s the full circle, etched in smoke rings and steel strings. From Abbott’s dust to Austin’s glow, the outlaw rides home—not alone, but arm-in-arm with the ghost who got him gone. And in that closing, American music finds its heart: broken, braided, unbreakable.