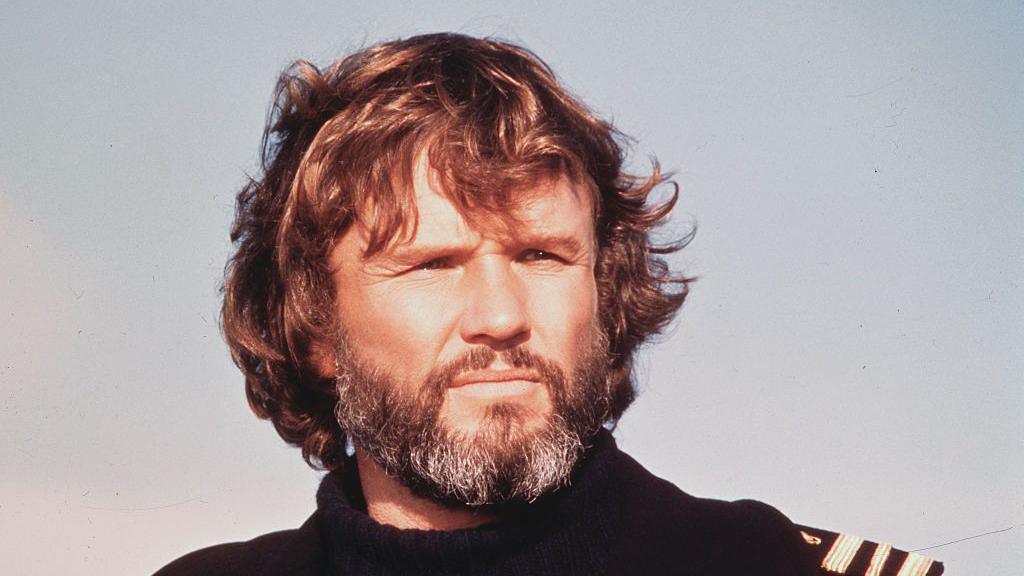

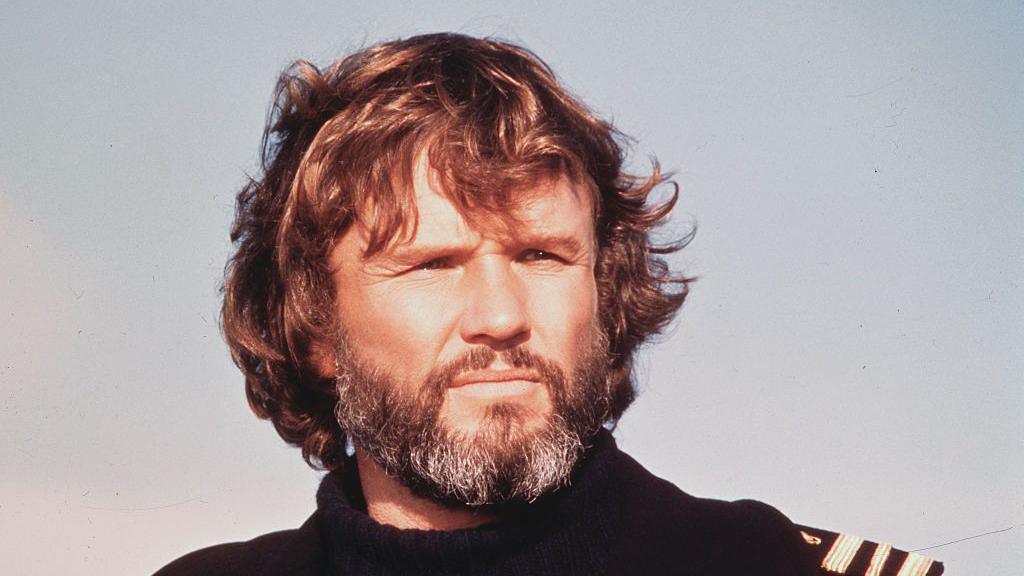

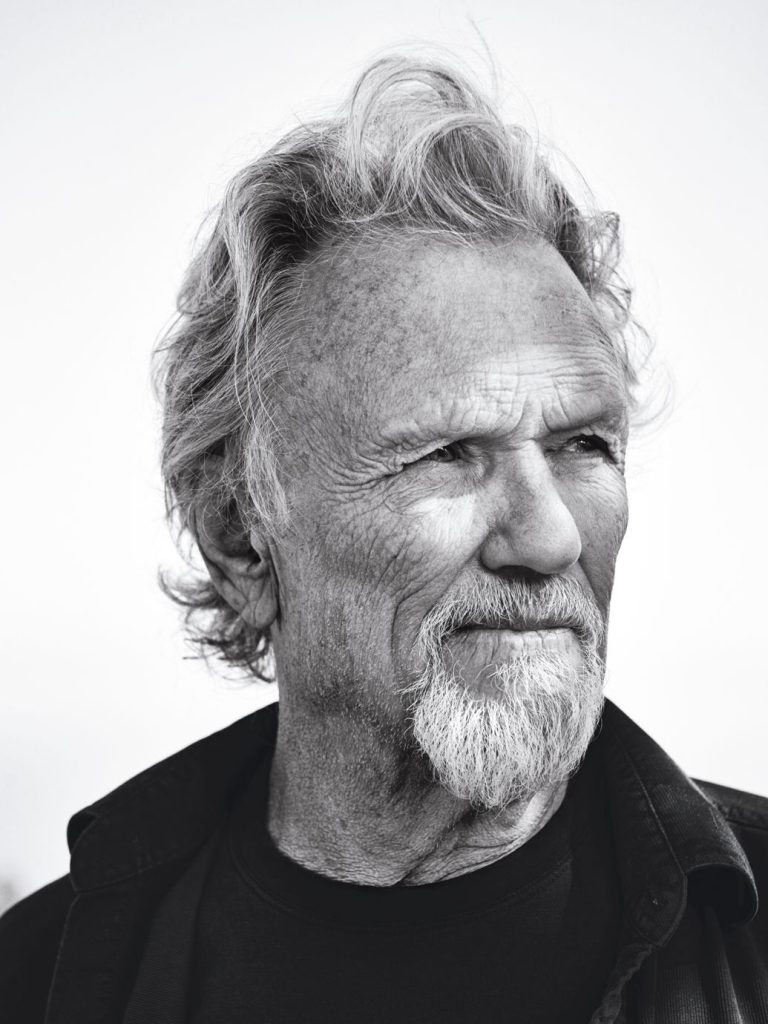

When Kris Kristofferson picked up a guitar, it wasn’t just music he was making. It was confession. It was testimony. It was the voice of people most of us never saw—or refused to see. Unlike other songwriters who chased hits or fame, Kristofferson wrote from the edges of humanity. He sang about drifters, lovers clinging to broken dreams, the working man who came home to disappointment, and the woman who gave too much and was left with nothing. His stories were raw, unpolished, sometimes painful to hear—but they rang true in ways that silenced a crowd.

What made Kristofferson extraordinary wasn’t only his gravelly delivery or poetic phrasing—it was his empathy. He could inhabit another life, slip into another soul, and sing as if he had lived it himself. The mystery is how he did it. Was it imagination? Observation? Or was it a reflection of wounds he carried deep inside, scars that never healed but transformed into words?

A Poet Among Outlaws

Kristofferson’s rise was improbable. A Rhodes Scholar, an Army pilot, and son of a strict military family, he seemed destined for a respectable, rigid path. Yet he threw it all away—literally walked away from privilege and predictability—to chase music in Nashville, where he cleaned floors as a janitor at Columbia Records just to be near the songs. That decision, reckless to many, was the first sign of his empathy. He chose to live closer to those who struggled rather than distance himself with titles and accolades.

And so when he wrote Sunday Morning Coming Down, he wasn’t just describing a hungover morning. He was painting the portrait of loneliness, of the man who looks around and feels emptiness closing in. The beauty of that song lies in its universality—you didn’t have to be drunk or broke to understand it. Everyone knew what it felt like to wake up hollow.

Voices of the Forgotten

Kristofferson’s catalog is filled with outsiders. Darby’s Castle tells of obsession, ambition, and ruin—a metaphor for men who build their lives on fragile dreams. Help Me Make It Through the Night gave voice to yearning, to the human craving for closeness even when love was imperfect. And Me and Bobby McGee, immortalized by Janis Joplin, is the anthem of restless freedom and heartbreaking loss.

He wasn’t afraid to shine light on the gritty truths: the alcoholic looking for solace, the drifter searching for a home, the woman judged for her desires. In a time when much of country music glorified clean-cut ideals, Kristofferson was almost dangerous. He wrote about real people—flawed, broken, beautiful in their imperfection.

Fans often said it felt like he wasn’t just writing about them; he was writing for them. He gave dignity to people who had none.

The Mystery of His Empathy

But where did it come from? How did a man raised in military precision find his way into the hearts of those so far from his background?

Some biographers suggest it was his natural curiosity. Others point to his years of struggle in Nashville, where he lived in a rundown apartment, watched friends fail, and understood the quiet desperation of chasing a dream.

Yet those who knew him personally say it was more intimate. Kristofferson carried an ache—a loneliness he rarely admitted, an insecurity buried beneath his achievements. That ache gave him insight into the pain of others. When he sang their stories, he wasn’t just imagining; he was confessing in code.

Empathy as Rebellion

In many ways, his empathy was an act of rebellion. The world he left behind—academia, the Army, and the promise of prestige—demanded perfection and control. By writing about broken people, Kristofferson was pushing back, insisting that the imperfect had value. That the man on the street corner mattered as much as the general in uniform.

This is perhaps why his songs found a home with other outlaws—Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings. Together, they weren’t just making music. They were challenging a system that polished away the rough edges of humanity. Kristofferson, with his poetic grit, gave that rebellion its soul.

A Hidden Confession?

There’s a haunting theory among fans and critics: that Kristofferson’s empathy wasn’t just compassion—it was self-portraiture. His songs weren’t only about strangers. They were about him.

Take For the Good Times. On the surface, it’s a farewell ballad of kindness after love fades. But listen closer, and you hear a man pleading not to be forgotten. It’s hard not to wonder if Kristofferson was speaking to his own fears of being abandoned, dismissed, or misunderstood.

Or Why Me Lord, a gospel plea written at a time of personal turmoil. It sounds like gratitude, but beneath it lies guilt, unworthiness, the sense of a man who never felt at peace with himself.

Perhaps his empathy came because he lived on the same fragile ground as those he wrote about. He, too, was searching. He, too, was afraid.

Legacy of Empathy

Today, Kristofferson’s legacy stretches far beyond country music. He proved that songs could be more than entertainment—they could be literature, testimony, even salvation. Many young songwriters cite him not just for his lyrics, but for his bravery in writing about pain.

Empathy is rare in a world obsessed with image and perfection. Kristofferson carried it like a torch. And in doing so, he illuminated lives that might have been left in darkness.

The Final Question

But here’s the most haunting thought: Did Kris Kristofferson pay a price for his empathy? To feel so deeply, to absorb the pain of the forgotten, surely took something from him. Was the gravel in his voice only the sound of age—or was it the weight of every story he carried?

We may never know how much of himself he poured into the lives of others. What we do know is that he left us with songs that continue to echo in lonely rooms, crowded bars, and quiet nights.

And maybe that’s the true gift of his empathy: that even now, long after the last note fades, someone who feels invisible can hear his words and realize—they were seen all along.